History

In the early 1950s Robert Riddles was the British Railways Executive for Mechanical and Electrical Engineering and he was responsible for the introduction of a range of simple, two cylinder standardised steam locomotives intended to be in service until the 1970’s.

Design and working life

The Duke was designed at Derby locomotive works in 1953 and was constructed at Crewe locomotive works in 1954. After approximately eight years’ service during which the locomotive enjoyed, at best, a mixed reputation on the main line, it was withdrawn and sent for scrap.

That bald story, although correct, gives no clue as to what makes the Duke unique and why it holds such a special place in the history of steam locomotive development in Great Britain. “Unique” is a much overused word in connection with many artefacts, but this particular locomotive probably better earns that epithet than any other.

In the early 1950s Robert Riddles was the British Railways Executive for Mechanical and Electrical Engineering and he was responsible for the introduction of a range of simple, two cylinder standardised steam locomotives intended to be in service until the 1970’s. There was no need for a new range of express passenger locomotives as the private railway companies, which had been nationalised in 1947, had left the newly formed British Railways well provided for. However, an unfortunate accident at Harrow in 1952 resulted in the scrapping of one of the ex-LMS pacific class locomotives, which thus presented Riddles with an opportunity to design a prototype for the future.

Caprotti

Caprotti rotary valve gear had, in the years immediately after World War Two, been brought to a state of much improved efficiency by the British company Associated Locomotive Equipment and indeed had been successfully fitted to two LMS Black 5 locomotives. Riddles (an ex-LMS man) elected to fit his prototype with British Caprotti rotary valve gear and, moreover, to fit his prototype with three cylinders. Riddles himself said, some years later, that the opportunity to build a “one-off” with Caprotti valve gear, eliminating or overcoming all the faults of reciprocating valve gear, giving constant valve openings at all times coupled with free exhaust, was too good a chance to miss.

Thus with these principles laid down, Derby drawing office set to work on the detailed design, once Riddles had received approval for his plan from the British Railways Board. They indicated that what they envisaged was an enlarged Britannia Class Pacific, using as many common parts as possible, and essentially that is what Riddles delivered. Although Derby was responsible for the main design work, Swindon drawing office was asked to design the exhaust system. The representative from the Associated Locomotive Equipment Company, Mr Tom Daniels, had enjoyed close contact with the noted French steam locomotive engineer Andre Chapelon, as a result of which the company was the agent for the patented Kylala-Chapelon double blastpipe exhaust system. Tom Daniels felt that this Kylchap system was what was needed for optimum draughting in conjunction with the rotary Caprotti valve gear. However, possibly in the light of patent costs, this advice was ignored and Swindon produced a plain, bifurcated, blastpipe with double chimney. It has been suggested that the dimensions were simply a double version of that found on the Great Western Dean goods locomotive and, perhaps not surprisingly, Tom Daniels was disappointed at this outcome. The Duke subsequently ran with the Swindon designed double blastpipe and chimney for the whole of its short career on British Railways.

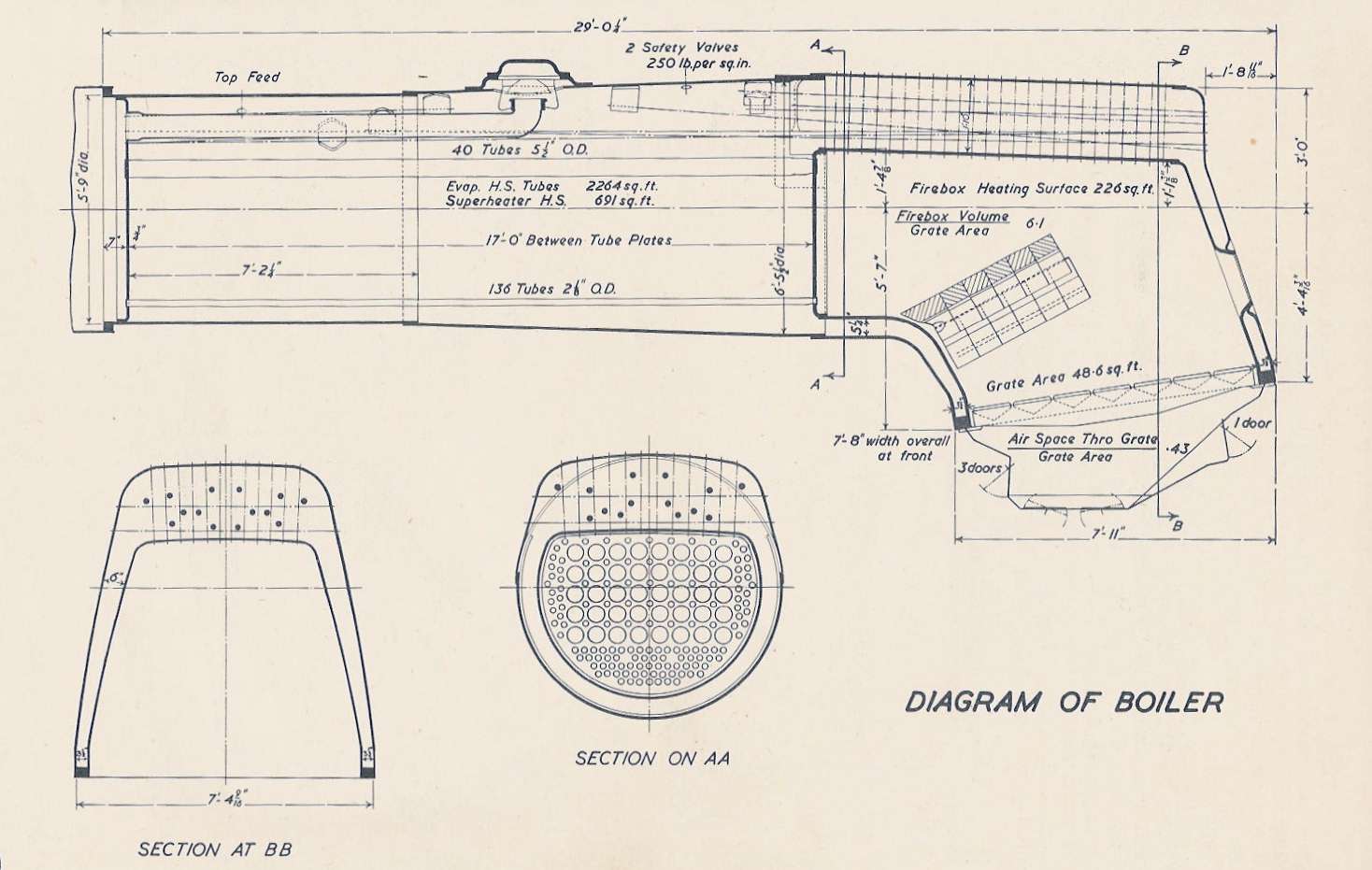

Both on test and in service the locomotive boiler was found to steam freely, although at the expense of high coal and water consumption, however the British Caprotti valve gear did everything that had been expected of it. Crewe North depot became the Duke’s home once in service where it was rostered for the same work as Crewe’s beloved Stanier Pacifics, which may, in part, explain some of the antipathy which developed towards the Duke. There is no doubt that, given a sympathetic crew, the Duke was more than capable of handling the same work as the Stanier Pacifics, but without, regrettably, the same consistency of performance. That there was a deep seated flaw was quickly detected by the enginemen of Crewe North depot. Some said that the loco tended to be “shy for steam”, others that it “ate coal” whilst there were still others who loved the loco. One fireman who suffered no steaming problems is on record as saying that he fired the Duke in the same manner as he fired a three cylinder Royal Scot – a well built up fire under the back corners of the firebox plus a bit extra under the brick arch to keep the firebed down on the firebars. This is a totally different technique to that used by firemen on the four cylinder Stanier Pacifics where, basically, on long runs the fire was built up on the depot, until the firebox was filled with coal of any size up to the level of the fire hole doors. This treatment apparently did not suit the Duke one bit, which might have added to the reputation of being “shy for steam”.

Steaming irregularities and coal appetite aside, that the locomotive could both pull and run was without question, which is probably why the Duke was often to be seen at the head of the Mid-Day Scot. However, Crewe’s enginemen, despite their understandable allegiance to Stanier’s pacifics, were correct in their view that there was something not quite right about the locomotive.

In 1955, the year after the Duke was constructed; British Railways published their Modernisation Plan which heralded a future based around diesel and electric traction, and in so doing sounding the death knell for steam traction in the UK. There was thus neither the money nor the will to get to the bottom of what ailed the Duke, which was left to soldier on, frustrating numerous crews, until being withdrawn from service, along with the remaining Stanier Princess Royal pacifics, at the end of the 1962 summer timetable. The Duke was then unceremoniously dumped on Crewe North depot whilst its fate was decided. E. S. Cox, assistant to Robert Riddles during the introduction of the B. R. Standard classes of locomotive, described the Duke as a “near miss”.

British Railways had listed the Duke for official preservation as part of the National Collection, but for reasons which are now unclear, that decision was later changed to simply retaining one sectioned cylinder plus its associated rotary valve gear.

Barry

The right hand cylinder was removed at Crewe Works and used as a “guinea pig” for the final sectioning of the left hand cylinder which was later exhibited at the Science Museum, South Kensington, London. This sectioned cylinder together with its valve gear currently resides at the Heritage Centre, Crewe. Shorn of its outside cylinders and other fittings the remainder of the locomotive was then sold for scrap. Initially towed to Cashmore’s, Gwent for cutting up it was only by pure chance that a former BR fireman, Maurice Sheppard, on visiting Cashmore’s yard in connection with his work, noticed that the destination label on the Duke read “Woodham’s, Barry”. He realised that the remains had been taken to the wrong destination and was instrumental in ensuring that the remains of the Duke were towed to their correct purchaser – Dai Woodham of Barry.

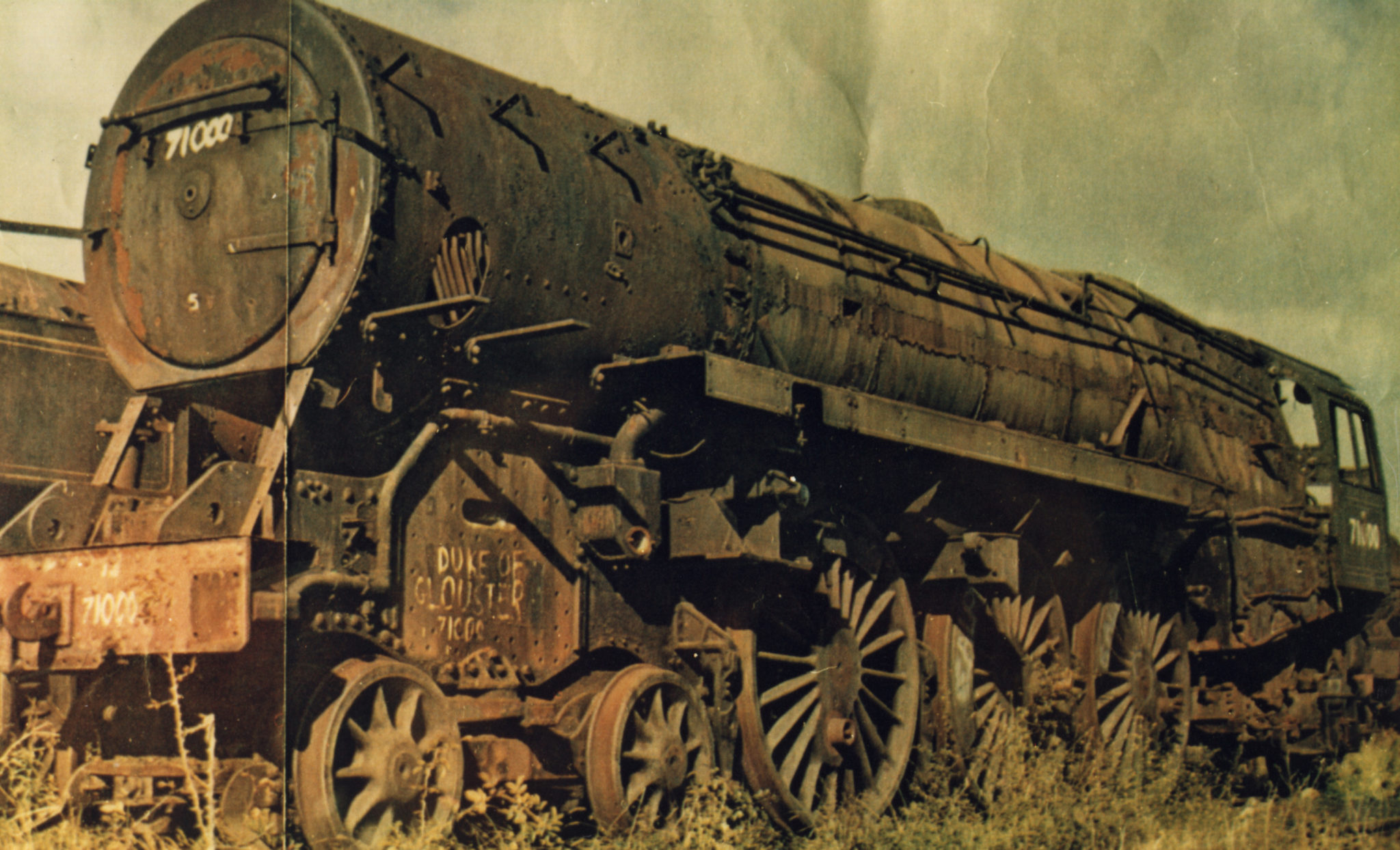

The Duke subsequently stood at Barry for seven years and, by 1973, consisted of little more than boiler, frames, inside cylinder (minus cambox), wheels, cab frame and rusting cladding. Souvenir hunters, other preservationists and the salty sea air had turned the once proud standard bearer for steam’s future into a forlorn and pitiful sight. Even its tender had been sold off to a South Wales steelworks where its chassis was used for the transportation of steel.

By 1973 the phenomenon of small groups purchasing rusting hulks from the large dump of ex – BR locos sitting at Barry scrapyard, for restoration and further use, was already under way. However, in the case of the Duke it was generally thought that the technology, skills and knowledge necessary to re-manufacture the two outside cylinders, together with their unique valve gear, was long gone. In any case, the likely cost would be prohibitive and anyway, the locomotive had proved unsatisfactory when in service, so what would be the point?

Restoration

At the beginning of 1973 a small group was formed and a member of that group, Colin Rhodes, advertised for members and out of this the 71000 Preservation Society was born. To say that they were regarded as hopeless optimists chasing an impossible dream would be an understatement. A chance meeting with Hugh Phillips enabled the group to make significant progress as Hugh was a Caprotti enthusiast and had access to photographs of every drawing of the poppet valve gear. At that time the drawings were kept by Froude Engineering of Worcester who had manufactured the original equipment. Perhaps even more importantly, he had an introduction to Tom Daniels who, at the time of the Duke’s construction, was, as mentioned above, the representative from the Associated Locomotive Equipment Company which supplied all the original Caprotti valve gear. His wealth of knowledge and experience was to prove invaluable.

Initial fund raising by the group proved almost impossible given the widespread scepticism on the part of enthusiasts generally, and the Association of Railway Preservation Societies in particular. At the end of six months the princely sum of £124 had been raised. It was therefore proposed that Society members put their own money into the scheme in blocks of £100 and, to facilitate this, a limited company was formed. More than thirty members accepted the offer of shares in the company and, within three months, the sum of £4,950 had been paid to Woodham’s for the locomotive plus a tender from a 9F. The hulk was given a cosmetic coat of green paint plus smoke deflectors and double chimney, also from a 9F. On the 24th April 1974 the Duke, looking smarter than for many years, left Barry for its new home at the Great Central Railway, Loughborough, Leicestershire, so be followed seven months later by its new tender.

The steps necessary to restore the Duke were divided into clear sections, each having a team leader and with specific tasks to carry out, with Colin Rhodes providing overall control and operating as a significant driving force. The restoring group had taken the decision at the outset that the locomotive was to be completely dismantled and rebuilt into “as new” condition and so they set out on their mammoth task. The project can, perhaps, only be properly described or indeed understood by those individuals who, over a number of years, faced and surmounted challenge after challenge. Here, again, we come up against that word “unique” as no other preservation/restoration group can have faced such hurdles, scepticism, derision or general shaking of heads. Nonetheless, throughout all of this the group ploughed forward, steadily making progress and gradually confounding their critics. Initially the only institution to offer meaningful financial assistance was the Science Museum which, perhaps for obvious reasons, donated the large sum of £6,000 towards the cost of new cylinders and valve gear and Crewe Borough Council (as it then was) also made a financial donation. Once it had become clear that the restoration group was serious and was indeed making progress, even the previously dismissive Association of Railway Preservation Societies decided to grant the group Associate Membership status and, after that, offered all possible support.

In 1977 the 71000 Preservation Society gave way to two newly registered bodies – 71000 Steam Locomotive Ltd and The 71000 (Duke of Gloucester) Steam Locomotive Trust, a registered charity. The former of these two new entities became the registered owner of the Duke, the intention being that interested parties could buy shares in the new Company and thus enjoy part ownership of this unique (that word again!) cultural asset. The owning Company, by way of a Deed of Trust, passed responsibility for the upkeep, maintenance and running of the Duke over to the newly registered Trust for a period of Fifty Years.

A full description of the work involved in taking the rusting and stripped hulk of the Duke back to a fully operational locomotive can be found in Peter King’s comprehensive pamphlet entitled “71000 Duke of Gloucester the Impossible Dream” published by Ian Allen in 1987. Much of the above factual information has been obtained from Mr King’s work. Suffice it to say that the locomotive eventually returned to steam at the Great Central Railway in May 1986, initially without its rear coupling rods, and formal re-commissioning of the locomotive was undertaken by His Royal Highness The Duke of Gloucester at Rothley station on the 11th November 1986. Rightly he praised the irrepressible determination, resourcefulness and individual skills that had brought about the resurrection of this great locomotive.